Catastrophes, wars, terrorism, ecological disasters, deadly diseases, poverty .... The list of tragedies - both personal and public - is endless. Every day and hour media, politicians, experts - and charlatans - bring us a never ending barrage of bad things. No wonder that many people feel depressed and weary. This blog tries - in a modest and personal way - to contribute to a more balanced view. After all, there is so much to appreciate and enjoy in life ...

Showing posts with label maps. Show all posts

Showing posts with label maps. Show all posts

Friday, 21 December 2012

A 1626 map of Finland

Old maps are beautiful. This map of Finland from 1626, made by Andreas Bureus (1571-1646), the founder of Swedish scientific cartography is one of my favorites. (Finland was until 1809 a part of Sweden).

Saturday, 22 September 2012

The Swedish merchant fleet during World War 1

|

| Some Swedish merchant ships were marked with a flag showing the Swedish colours |

Neutral Sweden was not a participating nation in the World War 1, but still the country was in many ways affected by the war. Particularly, the Swedish merchant fleet was hit quite hard; during the war years it lost altogether 194 ships, 17% of its total tonnage.

|

| 1918 map of submarine blockade zones |

|

| German, Danish and Swedish mine fields in Øresund (1916) |

|

| A German U-boat holding up a Spanish steamer |

|

| The Swedish steamer Hispania had a white and red zebra painting, indicating that it was entitled to sail through the U-boat zone when departing the UK. |

|

| Workers inspecting damage caused by a mine on the Swedish steamer Thyra in April 1919 |

|

| In July 1917 the Swedish steamer Vanland was hit by a torpedo |

|

| In March 1916 the steamer Martha hit a mine field close to the Falsterbo reef, but could be towed to Malmö |

(Source: Article by Axel Lindblad in the book Sveriges Sjöfart, published in 1921)

Wednesday, 12 September 2012

Two old maps of Øresund

"A most detailed depiction of the Danish arm of the sea Øresund"

Etching from the 1580s, included in G. Braun´s and F. Högenberg´s

Monday, 26 September 2011

Tycho Brahe´s map of the island Hven

This map of the Swedish island Ven (or Hven in Danish) is the only map that the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546 - 1601) personally drew. It is also the first map in Scandinavia which is based on systematic measurements. The map was included in Brahe´s Epistolanum astronomicum libri from 1596.

At the the time Brahe produced his map, he was living and working on the then Danish island Hven, which had been given to him by king Frederik II. The island is situated in the Øresund strait between Scania (Sweden) and Zealand (Denmark).

|

| Tycho Brahe built two observatories - Uraniborg and Stjerneborg - on Hven |

|

| Tycho Brahe working in Uraniborg |

At the the time Brahe produced his map, he was living and working on the then Danish island Hven, which had been given to him by king Frederik II. The island is situated in the Øresund strait between Scania (Sweden) and Zealand (Denmark).

Thursday, 20 January 2011

Antique maps

.

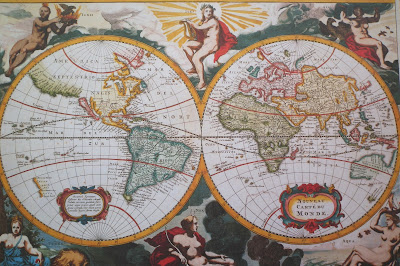

Nova Delineatto Totius Orbis Terrarum Per Petrum Vander Aa. (18th century)

'Journey all over the universe in a map, without the expense and fatigue of traveling, without suffering the inconveniences of heat, cold, hunger, and thirst.'

Miguel de Cervantes

Don Quixote (1605-15).

I have always been fascinated by old maps. Their beautifully drawn, hand coloroured details are pleasing to the eye. At the same time antique maps illustrate bygone times in a stimulating way. One also must admire the skill of the famous mapmakers who were able to produce quite accurate maps at a time when there were no GPS or other advanced technical instruments at their disposal. Of course, even the best mapmakers - like Gerard Mercator and Abraham Ortelius - tooks certain liberties, as Mathew Lyons points out in his very readable little book "Impossible Journeys":

"Not content to rely on gossip they picked upon quaysides, or scraps of third-hand information allegedly culled from antique texts, the mapmakers had no ethical problems when it came to inking in areas on their maps that they thought ought to exist. While our understanding of mapmaking would usually be confined to the careful marking of the known, medieval and Renaissance cartographers had a rather more generous conception of their role.They were philosophical geographers. Worse, perhaps, they were theoretical philosophical geographers. They liked to extrapolate, on the basis of fashionable theory, what might be out there, still undiscovered. While some were happy to let unknown coasts stay unmarked - the unbroken lines of peninsulas, points and coves tailing off, like loose threads or trains of thought, in open space - others had no apparent qualms about setting down their ideas and sending them out into the world, as if to say `This is so.´

Lyons goes on to name some interesting examples of early "creative" mapmaking, like e.g. Terra Australis Incognita (corresponding to Antarctica), which figured in different forms in many famous maps, although no human being is known to have seen Antarctica before 1820.

Detail from map of the Turkish Empire, 1606

Map of Moscow, 16th century

PS

If you are interested in learning more about old maps, the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin is a good place to start.

Nova Delineatto Totius Orbis Terrarum Per Petrum Vander Aa. (18th century)

'Journey all over the universe in a map, without the expense and fatigue of traveling, without suffering the inconveniences of heat, cold, hunger, and thirst.'

Miguel de Cervantes

Don Quixote (1605-15).

I have always been fascinated by old maps. Their beautifully drawn, hand coloroured details are pleasing to the eye. At the same time antique maps illustrate bygone times in a stimulating way. One also must admire the skill of the famous mapmakers who were able to produce quite accurate maps at a time when there were no GPS or other advanced technical instruments at their disposal. Of course, even the best mapmakers - like Gerard Mercator and Abraham Ortelius - tooks certain liberties, as Mathew Lyons points out in his very readable little book "Impossible Journeys":

"Not content to rely on gossip they picked upon quaysides, or scraps of third-hand information allegedly culled from antique texts, the mapmakers had no ethical problems when it came to inking in areas on their maps that they thought ought to exist. While our understanding of mapmaking would usually be confined to the careful marking of the known, medieval and Renaissance cartographers had a rather more generous conception of their role.They were philosophical geographers. Worse, perhaps, they were theoretical philosophical geographers. They liked to extrapolate, on the basis of fashionable theory, what might be out there, still undiscovered. While some were happy to let unknown coasts stay unmarked - the unbroken lines of peninsulas, points and coves tailing off, like loose threads or trains of thought, in open space - others had no apparent qualms about setting down their ideas and sending them out into the world, as if to say `This is so.´

Lyons goes on to name some interesting examples of early "creative" mapmaking, like e.g. Terra Australis Incognita (corresponding to Antarctica), which figured in different forms in many famous maps, although no human being is known to have seen Antarctica before 1820.

Detail from map of the Turkish Empire, 1606

Map of Moscow, 16th century

PS

If you are interested in learning more about old maps, the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin is a good place to start.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)